Our Stories

The stories below are voluntarily provided by stateless people in our network. These accounts show the various forms of statelessness in the European Union. Should there be any questions or interest in further detail about any story, or if you are stateless and would like to share your story, please feel free to contact us. New stories are welcome and will be continually added.

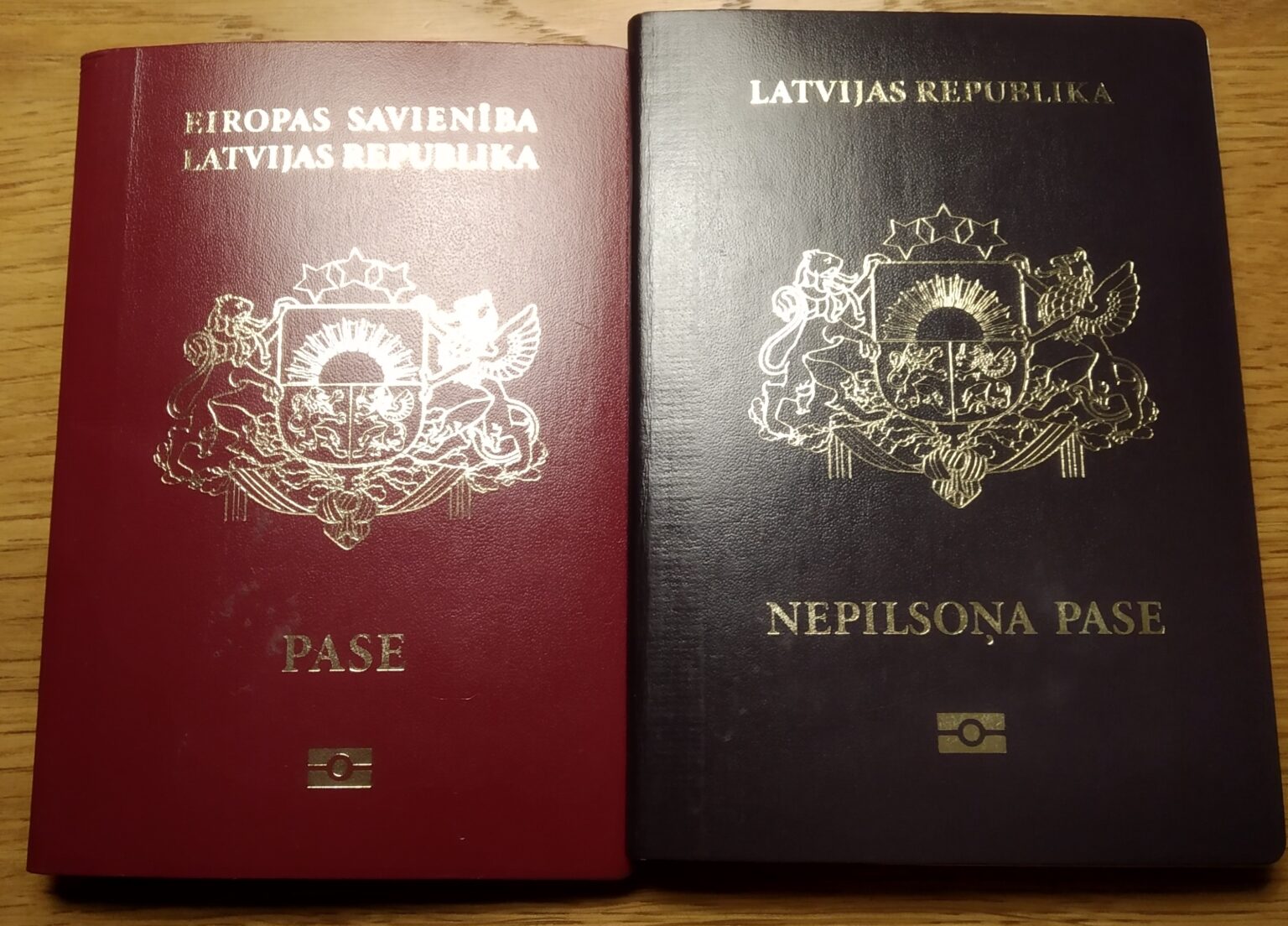

Aleksejs was born in Riga, Latvia. Not long after his birth, Soviet Union collapsed and Latvia became independent. Contrary to the pre-independence assurances, the country’s leadership declared that the minorities are not to have equal access to citizenship. Aleksejs’ family was among the seven hundred thousand other people that became effectively stateless in their own country.

Although from an early age Aleksejs grew up in the United States and Canada, in 2016 he made a difficult decision to move back to his home continent of Europe. He was influenced by Latvian claims that there are basically no differences in rights between Latvian citizens and Latvian “non-citizen”; and he also assumed that the EU member states would not undermine their own fundamental principles and values by importing arbitrary discrimination. But upon returning to Europe, he discovered many barriers due to his Latvian “non-citizen” status, especially given its contradictory nature of being de facto but not de jure nationality.

Aleksejs is a recognised expert on statelessness. He leads Apatride Network, delivers guest lectures at universities, provides training for lawyers, and collaborates with international organisations such as UNHCR and Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion (ISI). He is also an associate member of European Network on Statelessness (ENS) and European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST).

You can read more about Aleksejs’ story here.

Despite the fact that Christiana was born in Munich, Germany, she’s been affected by statelessness since birth. While she’s recently been recognized as a stateless person, her previous status was defined as “undetermined nationality” and hindered her from obtaining a passport until she turned eighteen.

As a person affected by statelessness, Christiana has oftentimes struggled with the invisibility of the issue as well as the lack of information. Up until summer of 2020, Christiana had never met any other person who knew about the topic of statelessness, let alone someone who was affected by it. The most frustrating part for Christiana was the fact that as a person affected by statelessness, people often lack the chance to fully understand their rights and opportunities in life.

Christiana is an activist and recent founder of statefree.world – a digital initiative to create community between stateless people and their allies.

You can read more about Christiana’s story here.

Tatiana was born in Latvia. Her father was also born there, in 1951. Tatiana’s mother was originally from the far east of Russia, she moved to Latvia after falling in love with Tatiana’s father. The whole family became “non-citizens” along with many other minorities in the Baltics, due to sudden and unexpected political changes in the country.

Tatiana came to Czech Republic in 2013, meeting her future husband there. Czech authorities gave Tatiana a residence permit, based on a decision that she was born in Latvia and was accordingly from there. However, within a year Tatiana received a letter about a sudden reversal of decision on her residence in Czech Republic.

Tatiana expresses frustration over how her status is ill-understood, even by the relevant authorities. The lack of information about regulations in respect to non-citizens is not just a problem for the non-citizens themselves; it is also a problem for the authorities outside of Latvia.

The status also creates unusual problems with employers outside of Latvia, creating uncertainty on how to legally categorize a person in order to hire him or her. Although people like Tatiana are long-term residents of the EU, they lack the same rights as other EU residents.

Nowras is a stateless scientist who was born as a stateless refugee in Syria in 1993. Despite the disadvantages, he was able to pursue his education, which became a key lifeline from statelessness. Major part of his education, as a child, was in a primary UNRWA school in Damascus. He obtained a bachelor’s degree in Pharmaceutical Chemistry from the University of Damascus in 2016. He left Syria after seven years of witnessing the Syrian civil war atrocities.

Arriving in Germany in 2018, Nowras continued his studies, undertaking a master’s degree in Nanoscience at the University of Kassel. In 2020, he joined a research group at the Max Planck Institute and contributed to the development of a vaccine candidate for the SARS-CoV2 (Covid-19) pandemic. Shortly after, Nowras graduated with a master’s with the highest possible achievement and moved to Vienna, Austria, to start a Ph.D. programme in Nanomedicine. He is determined to raise more awareness on statelessness and to advocate for the rights of those who lack nationality.

You can read more about Nowras’ story here.

Jawad is a Bahraini MP who was one of the first victims of Bahrain’s citizenship revocation, which was used as a punitive measure against hundreds of Bahraini nationals for opposing the government in the 2011 Bahraini anti-government protests. The citizenship revocation has been officially formalized in 2014, when the Bahraini authorities amended the 1963 Citizenship Law to allow the government to revoke citizenship from those who were deemed a threat to state security.

Following the 2011 Bahraini anti-government protests, due to his belonging to the popular opposition movement, Jawad was subject to arrest, torture, and maltreatment of relatives. Jawad was eventually released from detention. However, a year later, on his trip to the United Kingdom, he received word that the Bahraini government stripped him of his citizenship. Jawad remains in exile in the U.K. to this day.

Under the threat of citizenship revocation, Bahrainis have been restricted in the exercise of their rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and belief. Jawad emphasizes that citizenship is the most basic and fundamental right of every individual. It is a right of rights; a right which, when possessed, could unlock other rights, and whose absence erodes enjoyment of all rights and protection. The possession of citizenship should not be understood as privilege or reward for allegiance, and its revocation should not be wielded as a weapon of control and oppression.

You can read more about Jawad’s story here.

Marina was born in Jurmala, Latvia, in 1962. Her father came to Latvia when he was a child, right after the Second World War, at the behest of his eldest sister who was posted in Latvia as a medic in a hospital. Marina lived in Latvia for all of her life, knowing no other country aside from tourism.

When Latvia was gaining its independence, Marina and her family voted for independence in the national referendum, truly believing in the assurances of equal rights and democratic freedoms. When people received their different passports, there was unease about the new segregation between Latvian citizens and Latvian “non-citizens.” Marina recalls believing, at the time, the assurances made by the authorities that there would be little difference between citizens and non-citizens in terms of rights (assurances that are made to this day, despite the reality to the contrary).

As a Latvian non-citizen, Marina is disappointed by how she cannot practice democratic rights. The last time she practiced these rights was when she voted for Latvian independence. Marina is also personally bothered by the inequalities in freedom of movement.

Marina considers naturalization, but she is bothered by the increasing difficulty of the naturalization exams and the politically charged nature of these exams. She finds it strange that she needs to go through naturalization in her own country.

Almontaser is a stateless person who came to Sweden in 2015 and applied for asylum. Since then he has been living in Sweden with his two children.

Almontaser has origins as a Palestinian who was born in Jerusalem. He received a permanent residence permit from Israel, and, due to how East Jerusalem once belonged to Jordan, Almontaser and his family held Jordanian citizenship. For employment reasons, Almontaser’s parents moved to Saudi Arabia in 1979, two years before his birth. The country became their primary place of residence for the family based on continual renewal of work permits (Saudi Arabia has highly restrictive residence and citizenship laws).

Trouble started for Almontaser and his family when, in 1996, Israel passed a law that anyone who lived outside of Jerusalem for seven years will lose permanent residence. In 2007, Almontaser went to Jordan to renew passport. To his surprise, he was asked to go to Jerusalem to renew the residence there, as it was connected with the Jordanian citizenship. But this was now impossible.

Jordanian authorities investigated the case and made a decision to withdraw citizenship from Almontaser and his whole family. Jordanian authorities declared Almontaser as a Palestinian. From that point onward, Almontaser and his family became stateless with dire need of a place to call home.

Lynn was born in Syria as a third-generation Palestinian refugee. Even though Lynn’s father was also born in Syria, nationality was not accessible to the family. In 2014, after the civil war started in Syria and the situation became drastically worse, Lynn and her family came to Sweden and applied for asylum.

Regrettably, the Swedish migration agency refused Lynn’s family application based on a judgement that Lynn’s mother is Lebanese. The Swedish migration officials were ill-aware of how Lynn’s mother is not able to pass on her nationality due to discriminatory policies of the countries involved.

In effect, Lynn was neither allowed to stay nor to leave Sweden since Lebanon refused to recognize her as a national. Lynn expresses frustration over the bureaucratic catch-22 situation. For years she has been fighting to prove her statelessness, to put spotlight on the issue so that people know about it, not least migration officials.

From an early age, Lynn learnt about identity papers and what it means to lack them. Being born and raised in Damascus, Syria, to a Palestinian father and Lebanese mother, left Lynn with a lot of identity crises and lack of belonging. Lynn remembers that it was a tough reality for a child to grow up with. Being a stateless youth puts pressures to achieve so much more than other people, just in trying to gain equality—all because you were not born with the same papers.

You can read more about Lynn’s story here.

Luca was born and lived all of his life in Rome, Italy. Luca’s father came to Italy in the 1970s as a sailor, accepting a fisherman vacancy in Nettuno. Luca’s mother came from Cape Verde to work as a housemaid in Rome. The couple met in the Italian capital and settled down there.

Italy has some of the most restrictive nationality laws in the European Union. Due to how Luca was born to migrant parents, at the age of eighteen Luca faced the difficult bureaucracy of having to apply for Italian citizenship within a one-year timeframe. By the time he was able to gather all the necessary paperwork, that timeframe already expired and Luca found himself in no man’s land in the only country he ever knew.

As a child of migrant parents, Luca was troubled by the racism that he faced. The difficultly of regularizing one’s status in Italy has only exacerbated the situation. Luca has faced the constant threat of arrest and deportation and has continued to deal with bureaucratic hurdles to try to gain any sense of normalcy.

You can read more about Luca’s story here.

Cheija was born and raised in a Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria. Her parents were exiled from Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony, after Morocco invaded the region in the 1975. Due to this conflict, many Sahrawis fled to Algeria.

Cheija moved to Spain in 2007 and therein applied for residence permit. As she did not receive a response, Cheija continued to look for other ways to legalize her stay in Spain, not least for university and work reasons. In 2013, after years of trying hard to a dignified legal path, she received the acceptance of a different permit: statelessness. That was Cheija’s first contact with the term. At first she faced it with denial, thinking of herself as a refugee rather than as a stateless person. But, due to her need of legal clarity and some way to start building her future, she had no other option but to accept it.

Cheija has faced difficulties due to her statelessness status. In 2015, when she was invited to Turkey to present a lecture about her situation, she was jailed and deported back to Spain. Cheija recalls being treated like a criminal, simply for being a stateless person. She realized how the value of a human being depends on the color of their passport. Born as a refugee, survived as an immigrant and now a stateless person, Cheija promised herself to dedicate her life to raise awareness about statelessness.

Prince is a victim of human trafficking. When he was a baby, he was taken from the U.S. to Europe by a gang of women traffickers. He grew up isolated from society at large, under deplorable conditions, believing that one of these women was his mother. In 1990, due to how the traffickers were unable to sell him, Prince was abandoned on the streets of Germany. To this day, he is stateless and undocumented.

In Germany, Prince’s status is “Ungeklärt,” which means a person with an undefined status. No official document comes with the status aside from a “Duldung” — a piece of paper that indicated the unclear nature of the person’s status. The Duldung is poorly recognized by the authorities and public at large, making it unusable as an identity document.

Despite the fact that Prince went through FBI interrogation and DNA check, went through Interpol and German state police questioning, and sought help from the U.S. National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, no progress was made in establishing Prince’s identity or normalizing his status. It does not help that when Prince tried to become more public and wrote about his story online, he received death threats from racists.

Prince feels like a non-existing human because he is not considered as a citizen of the U.S., Germany or any nation, and not even classified as a stateless person despite being de facto stateless.

Thugten has been stateless for his entire life. Born in Bhutan, he was compelled to leave his homeland due to political oppression and the country’s “one nation, one people” policy, which has disenfranchised the local minorities. Due to such risk to safety, Thugten and his family embarked on a challenging journey that led to UNHCR refugee camps in Nepal. There, the family endured a decade and a half of uncertainty alongside over 100,000 others from Bhutan who had been expelled or forced to flee their homes.

After many years in refugee camps, Thugten and his family were finally resettled in Denmark in 2009. However, the issue of statelessness continued to haunt them. Denmark’s stringent immigration and naturalization laws are a barrier for obtaining permanent residency and Danish citizenship.

The statelessness issue has profound ramifications on the lives of Bhutanese community in Europe. A sense of displacement continues to pervade in that community, hindering the vulnerable people’s ability to forge a complete identity and a true sense of belonging. Over 800 individuals continue to hold only temporary residence permits, forcing them to navigate the arduous renewal process every two years. Travel limitations and visa challenges further disrupt these people’s ability to freely visit friends and relatives, straining precious connections across borders.

Undeterred by difficult circumstance, Thugten is determined to make a difference, taking on the role of President of the Association of Bhutanese Communities in Denmark, a non-profit organization dedicated to empowering Bhutanese community, preserving its culture, and facilitating its integration into Danish society.

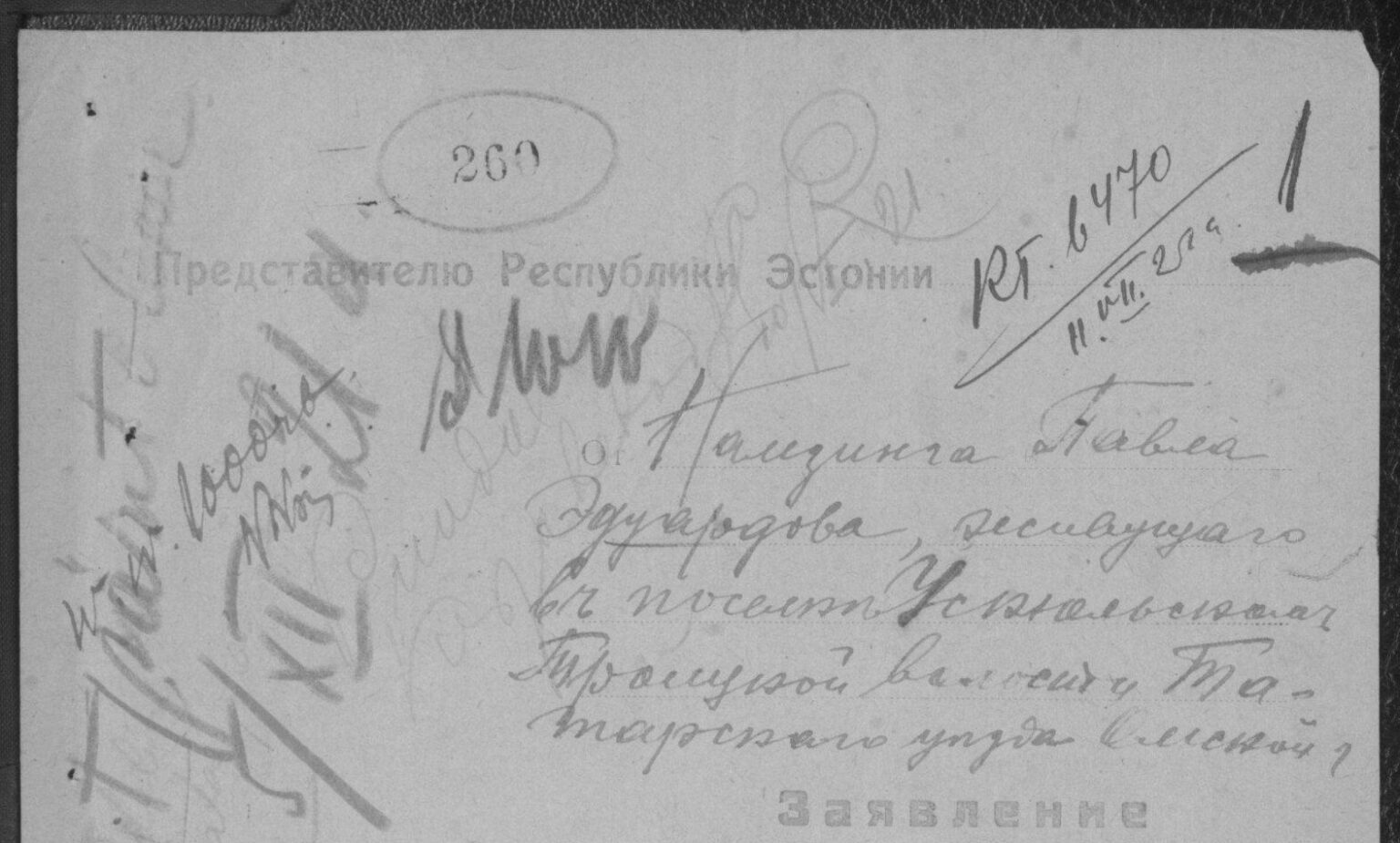

Alexander was born and currently resides in Tallinn, Estonia. Alexander’s paternal lineage goes back to a family of Estonians who moved to Siberia in the early 20th century. During the turbulent 1920s and 1930s, the family was left in obscurity when Alexander’s grandfather was arrested and disappeared. The remaining family members, led by the eldest son, traveled back to Estonia from Siberia. However, their travels were interrupted in the Tver region of Russia. It was only after WWII that the family was able to return to Estonia.

Like most Estonians, Alexander supported Estonia’s aspirations for independence from USSR, and looked forward to being part of the nascent nation. Regrettably, contrary to promises made, Estonian citizenship was granted selectively and restrictedly, in favor of those who could demonstrate descent from citizens of the Republic of Estonia that existed in 1918-1940.

Alexander’s wife and children have Estonian citizenship. This is due to how Alexander’s wife has roots in Petseri region of Russia, which was once part of the Republic of Estonia. Paradoxically, citizenship was extended to those born there, but not to the many born within Estonia’s borders.

Alexander is bothered by the discrimination that he faces due to his statelessness. The label “Alien” on his passport is a constant reminder of this discrimination. For minorities with such a status in Estonia, there is worsening sentiment and law, such as removal of minority children’s right to study in their native language and ongoing discussions about withdrawing the minorities’ right to vote in local elections. The recent deportations of stateless Estonians add to the many concerns that these minorities endured for more than three decades, furthering feelings of insecurity.